Recycling

three chasing arrows of the universal recycling symbol Recycling be de process wey dem de convert waste materials into new materials and objects. Dis concept often de add de recovery of energy from waste materials. De recyclability of a material dey depend on its ability to reacquire de properties wey eget for en original state. Ebe an alternative to "conventional" waste disposal wey go fit save material and help lower greenhouse gas emissions. Ego fit also prevent de waste of potentially useful materials and san reduce the consumption of fresh raw materials, reducing energy use, air pollution (from incineration) and water pollution (from landfilling).

Recycling be key component of modern waste reduction and ebi de third component of de "Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle" waste hierarchy.[1] Edey promote environmental sustainability by removing raw material input and redirecting waste output in de economic system. Dem get some ISO standards wey dey relate to recycling, such as ISO 15270:2008 for plastics waste and ISO 14001:2015 for environmental management control of recycling practice.

In ideal implementations, recycling a material dey produce a fresh supply of de same material—for example, used office paper go fit convert into new office paper, and used polystyrene foam into new polystyrene. Some types of materials, such as metal cans, go fit be remanufactured repeatedly wey en no lose en purity.[2] With other materials, dis be often difficult or too expensive (compared with producing de same product from raw materials or other sources), so "recycling" of many products and materials involves demma reuse in producing different materials (for example, paperboard). Another form of recycling be desalvage of constituent materials from complex products, due to either their intrinsic value (such as lead from car batteries and gold from printed circuit boards), or demma hazardous nature (e.g. removal and reuse of mercury from thermometers and thermostats).

History

[edit | edit source]Origins

[edit | edit source]

In pre-industrial times, there is evidence of scrap bronze and other metals being collected in Europe and melted down for continuous reuse.[3] Paper recycling was first recorded in 1031 when Japanese shops sold repulped paper.[4] For Britain dust and ash from wood and coal fires was collected by "dustmen" and downcycled as a base material for brick making. These forms of recycling were driven by de economic advantage of obtaining recycled materials instead of virgin material, and de need for waste removal in ever-more-densely populated areas.[5] In 1813, Benjamin Law developed de process of turning rags into "shoddy" and "mungo" wool in Batley, Yorkshire, which combined recycled fibers with virgin wool. De West Yorkshire shoddy industry in towns such as Batley and Dewsbury lasted from the early 19th century to at least 1914.

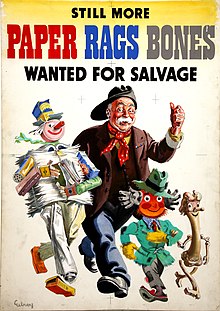

Industrialization spurred demand for affordable materials. In addition to rags, ferrous scrap metals were coveted as they were cheaper to acquire than virgin ore. Railroads purchased and sold scrap metal in the 19th century, and the growing steel and automobile industries purchased scrap in the early 20th century. Many secondary goods were collected, processed and sold by peddlers who scoured dumps and city streets for discarded machinery, pots, pans, and other sources of metal. By World War I, thousands of such peddlers roamed the streets of American cities, taking advantage of market forces to recycle post-consumer materials into industrial production.

| Material | Energy savings vs. new production | Air pollution savings vs. new production |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminium | 95% | 95%[6] |

| Cardboard | 24% | — |

| Glass | 5–30% | 20% |

| Paper | 40%[7] | 73% |

| Plastics | 70%[7] | — |

| Steel | 60% | — |

.mw-parser-output .reflist{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em;list-style-type:decimal}.mw-parser-output .reflist .references{font-size:100%;margin-bottom:0;list-style-type:inherit}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns-2{column-width:30em}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns-3{column-width:25em}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns{margin-top:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns ol{margin-top:0}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns li{page-break-inside:avoid;break-inside:avoid-column}.mw-parser-output .reflist-upper-alpha{list-style-type:upper-alpha}.mw-parser-output .reflist-upper-roman{list-style-type:upper-roman}.mw-parser-output .reflist-lower-alpha{list-style-type:lower-alpha}.mw-parser-output .reflist-lower-greek{list-style-type:lower-greek}.mw-parser-output .reflist-lower-roman{list-style-type:lower-roman}

- Ackerman, F. (1997). Why Do We Recycle?: Markets, Values, and Public Policy. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-504-5,

- Ayres, R.U. (1994). "Industrial Metabolism: Theory and Policy", In: Allenby, B.R., and D.J. Richards, The Greening of Industrial Ecosystems. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, pp. 23–37.

- Braungart, M., McDonough, W. (2002). Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. North Point Press, .

- Huesemann, M.H., Huesemann, J.A. (2011).Technofix: Why Technology Won't Save Us or the Environment, "Challenge #3: Complete Recycling of Non-Renewable Materials and Wastes", New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada, , pp. 135–137.

- Porter, R.C. (2002). The Economics of Waste. Resources for the Future. ISBN 1-891853-42-2,

- Sheffield, H. Sweden's recycling is so revolutionary, the country has run out of rubbish (December 2016), The Independent (UK)

- Template:RecyclingTemplate:Waste

- ↑ European Commission (2014). "EU Waste Legislation". Archived from the original on 12 March 2014.http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/legislation/a.htm

- ↑ Lilly Sedaghat (2018-04-04). "7 Things You Didn't Know About Plastic (and Recycling)". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 2023-02-08.https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2018/04/04/7-things-you-didnt-know-about-plastic-and-recycling/

- ↑ "The truth about recycling". The Economist. 7 June 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2008.http://www.economist.com/opinion/displaystory.cfm?story_id=9249262

- ↑ Cleveland, Cutler J.; Morris, Christopher G. (15 November 2013). Handbook of Energy: Chronologies, Top Ten Lists, and Word Clouds. Elsevier. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-12-417019-3. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2020.https://books.google.com/books?id=ScL77rOCZn0C&q=1031+japan+paper+recycling

- ↑ Black Dog Publishing (2006). Recycle : a source book. London, UK: Black Dog Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904772-36-1.https://archive.org/details/recycleessential0000unse

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedgar - ↑ 7.0 7.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedeconomistrecycle